Readings: Song of Solomon 2:8-13, Mark 7:1-8, 14-15, 21-23

Preached by Dr Emma Pennington at St Mary’s, Garsington and St Giles’, Horspath 30th August 2013.

It’s rare to hear the Song of Solomon read out in church on a Sunday morning. Somehow this wonderful love poem just doesn’t seem to sit well with the serious side of God and religion which we often think a church service is all about. Probably written to be performed at marriage festivals, it is to the same purpose that we often relegate it today. But why is it that this book, which the wise and eminent Fathers of the Church decided to include in the canon, causes us such trouble. The answer to this is clear, firstly, it is all about love. Not just any old love, but the really embarrassing kind of love, the love we find difficult to talk about or even mention anywhere near a church, yet as a church community we are often perceived as talking about all the time.

The other embarrassing thing about this word of God, is that God isn’t mentioned in it at all. Commentators have made some neat interpretive sidesteps and given it profound allegorical meanings to rectify this oversight. In turn it has been described as a picture of the love between Yahweh and Israel and Christ and the Church. Perhaps the greatest commentator of the latter is the twelfth century preacher and mystic Bernard of Claivaux whose series of sermons of the Songs used all the exegetical tools of his trade to paint a mystical and magical unfolding of Christ’s love for the soul.

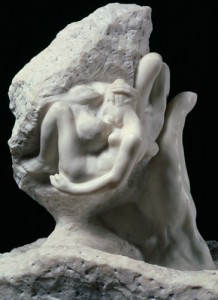

So what is it about this text, a beautiful erotic song of love that can help us know more about ourselves and our relationship with God whilst staying true to its content and form? The answer to this question, I feel can be found in another art form, sculpture. For me, the Song of Songs always reminds me of an amazing piece by Auguste Rodin called The Hand of God. I first saw it in the Musee Rodin in Paris and was transfixed by it, as have many others. Unlike his more famous work The Kiss, it is more mysterious and enigmatic as it reveals the profound spiritual depth of that most tender of human embraces. One cannot simply look at this sculpture but Rodin forces you to move around it before its meaning becomes clear. The marble he has carved is so sensuous and beautiful that he makes you want to caress it and in turn enter into this moment of love. For on one side of the sculpture there are two figures emerging from rough hewn stone. They seem intertwined in a passionate embrace even as they are being born out of the marble of which they are made. Some commentators have described these two figures as Adam and Eve who are created out of the primal sludge into the magnificent image of God. As you look at these two figures, his involvement in this act of creation cannot be seen.

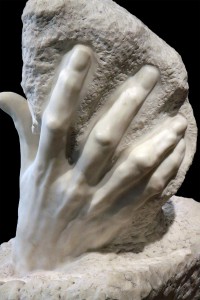

So what is it about this text, a beautiful erotic song of love that can help us know more about ourselves and our relationship with God whilst staying true to its content and form? The answer to this question, I feel can be found in another art form, sculpture. For me, the Song of Songs always reminds me of an amazing piece by Auguste Rodin called The Hand of God. I first saw it in the Musee Rodin in Paris and was transfixed by it, as have many others. Unlike his more famous work The Kiss, it is more mysterious and enigmatic as it reveals the profound spiritual depth of that most tender of human embraces. One cannot simply look at this sculpture but Rodin forces you to move around it before its meaning becomes clear. The marble he has carved is so sensuous and beautiful that he makes you want to caress it and in turn enter into this moment of love. For on one side of the sculpture there are two figures emerging from rough hewn stone. They seem intertwined in a passionate embrace even as they are being born out of the marble of which they are made. Some commentators have described these two figures as Adam and Eve who are created out of the primal sludge into the magnificent image of God. As you look at these two figures, his involvement in this act of creation cannot be seen.  It is not until you move to consider the sculpture from a different perspective that the hand of God comes into view, strong and powerful, yet tenderly moulding life and love, the eternal hand which holds the oblivious lovers in their embrace.

It is not until you move to consider the sculpture from a different perspective that the hand of God comes into view, strong and powerful, yet tenderly moulding life and love, the eternal hand which holds the oblivious lovers in their embrace.

I wonder if Rodin was inspired by the Song of Solomon to create this work. For the song itself, is a eulogy on the creativeness of love. The beloved and creation merge into one as he is described as coming like a gazelle leaping upon the mountains. He arrives at springtime, yet there is a sense in which it is his presence which causes the fig tree to put forth its figs, and the vine to blossom and give forth their radiance. God is not seen nor is he mentioned but his creative hand under-girds the transformative nature of the song revealing that human love and the whole of life exists within the context and perspective of its divine Creator, Lover and Sustainer, even when he is hidden or thought to be absent.

I once gave a postcard of this sculpture to a troubled student only to be later accused of promoting fornication. Of course this was the last thing from my mind, but it reminded me just how much we can encase the things of God within hardened rules and regulations that in fact take on a life of their own and forget the loving hand behind them. It was this that Jesus was so concerned about in our gospel reading. Not that the tradition of purification itself was a bad thing, but that it had come to replace the intention of living a holy and pure life. Jesus is not making an anti-religious statement but reminding the religious leaders of the day that the law of God is greater than our human constructs and it is within this perspective that religious practice is to be lived out.

When we were at St Pauls’ there was a very old man Maurice Beaven who had sung in the choir for over thirty years. He had written a tune to a hymn which I have only ever heard at that august place, and yet it is so beautiful and somehow it just goes to the heart of the words, drawing out their breadth and depth of meaning. The second verse of the hymn ‘There’s a wideness in God’s mercy’ just encapsulates what I think Jesus meant, ‘But we make his love too narrow/ by false limits of our own;/ and we magnify his strictness/ with a zeal he will not own. For the love of God is broader/ than the scope of human mind,/ and the heart of the Eternal/ is most wonderfully kind./ If our love were but more simple, /we should take him at his word;/ and our hearts would find assurance/ in the promise of the Lord.’ Maybe it is for this reason that the Song of Solomon is also held to be the word of God. Amen