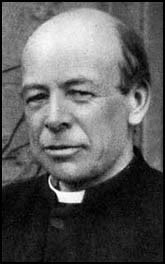

On 17th March it was the centenary of the death of Henry Scott Holland who is buried in the churchyard.  To honour this great man, Mark Chapman held a symposium at the college where a number of people gave papers on his life and work. In the afternoon a requiem mass was said for him and then prayers said over his grave. Below is the sermon which Mark preached and outlines not only his connection with Cuddesdon but also his historic sermon, parts of which are so often read out at funerals. I am very grateful to Mark for allowing me to put this in the newsletter.

To honour this great man, Mark Chapman held a symposium at the college where a number of people gave papers on his life and work. In the afternoon a requiem mass was said for him and then prayers said over his grave. Below is the sermon which Mark preached and outlines not only his connection with Cuddesdon but also his historic sermon, parts of which are so often read out at funerals. I am very grateful to Mark for allowing me to put this in the newsletter.

Henry Scott Holland died a hundred years ago today. After his funeral in Christ Church, his body was brought by motor hearse to Cuddesdon where he was buried on 25 March 1918. He had an enormous affection for the village, the college, and the church: he had been ordained deacon in this church on 23 September 1874 and towards the end of his life he spent much time in the village with his closest friend, Charles Gore, who was Bishop of Oxford from 1911 to 1919 and who lived in the palace over the wall. They had known one another from their earliest days: they were childhood neighbours in Wimbledon, and they maintained a deep friendship until Scott Holland’s death. Scott Holland said this at a College Festival: in ‘The old church with its quiet country look of patient peace’ the future clergy were taught to love God and serve the church:

Oh that we may go from Cuddesdon hill, every one of us, today, strong in the renewed communion of which our very denials have taught us to measure the true strength: go back with the voice of the Lord in our souls, re-enacting its choice, reasserting its desire that in Him alone, and by Him alone, we should set ourselves to find his flock and his sheep.

Scott Holland, of course, is a theologian who has become associated with death, and particularly with a popular reading which is part of a sermon called the King of Terrors. It begins like this:

I suppose all of us hover between two ways of regarding death, which appear to be in hopeless contradiction with each other. First, there is the familiar and instinctive recoil from it as embodying the supreme and irrevocable disaster. … There is no light or hope in the grave; there is no reason to be wrung out of it. Life is the only reality, the only truth. Death is mere blindness, mere negation. …

He then moves to the second aspect of death – the familiar quote:

there is another aspect altogether which death can wear for us. It is that which first comes to us, perhaps, as we look down upon the quiet face, so cold and white, of one who has been very near and dear to us. … And what the face says in its sweet silence to us as a last message from the one whom we loved is: “Death is nothing at all. It does not count. I have only slipped away into the next room. Nothing has happened. Everything remains exactly as it was. I am I, and you are you, and the old life that we lived so fondly together is untouched, unchanged”.

So death is “a supreme and irrevocable disaster” but it is also nothing at all. What did Scott Holland mean? To understand that requires knowing the context of the sermon.

At 11.45 pm on Friday, 6 May 1910, King Edward VII died of pneumonia. This came as an enormous shock to the country – he had, after all, returned from Biarritz only a few days beforehand, apparently in good health. On 2 May it was reported that he had developed bronchitis, but there seemed little special cause for concern. Although the general public did not know it, he was subject to frequent lung disease, presumably not assisted by his heavy smoking. By 5 May, however, the King was not well enough to receive the Queen on her return; and within another twenty-four hours he was dead. It could not have come at a more difficult time for the country. Politically, Britain was passing through one of its most turbulent periods. But the political crisis was temporarily halted by the sense of national unity which followed the shock of the King’s death. He was enormously popular which is probably what led the authorities to depart from precedent and to arrange for a public lying in state at Westminster Hall on 17 and 18 May. The King’s body was visited by at least 350,000 people, all of whom had to queue whatever their social status.

Scott Holland preached his sermon on 15 May, Pentecost Sunday while all this was going. He delivered it at evensong at St Paul’s Cathedral, where he had been a canon since 1884, and precentor since 1886. He happened to be canon-in-residence at the time, and it was only natural that should have preached on the king’s death. Many people felt such a close personal link with the King that his death was almost like a family bereavement. Scott Holland wanted to help people understand something of their emotions: death happens to all irrespective of their social status or public standing: “All are cut off by the same blind, inexorable fate – this death that we must die. It is the cruel ambush into which we are snared.” And with reference to the King, he asks: “Can any end be more untoward, more irrational than this?” Yet at the same time there was that other feeling which comes from the presence of the body itself: the calmness and serenity of the corpse lead to the inner conviction of a personal continuity which even death cannot destroy. Scott Holland goes on to reassure his congregation of the resurrection: in the power of the Spirit, he writes, we need not be afraid, for “when He shall appear we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is”. The love that was there in life still exists, but now in God: “Let the dead things go, and lay hold on life. … You will find yourself already passed from death to life, and far ahead strange possibilities will open up beyond the power of your heart to conceive.”

Years before Scott Holland expressed something similar after following the sudden death of his brother Lawrence in August 1893. He was a member of the volunteer reserve and died after suffering heat-stroke at the Aldershot military manoeuvres. Scott Holland wrote to his friend, Edward Stuart Talbot, later to be Bishop of Winchester, shortly after the funeral:

Once again, as with my father’s sudden death, the sight, the neighbourhood, the affectionate intimacy, have all served to diminish the fear, to make it seem but a little thing.

That quick short sigh: that ending of all that was painful, and sobbing, and strained: that slipping out with a look of relief and gentleness: that half-amused content on the quiet face the moment it is over—all serve to give instinctive continuity to the life that has gone.

It is just what it was. It has gone round the corner: in our midst: while we kneel round, and touch it. So close it must be! Just in the other room! Without surprise, it is there. It is hid, that is all. This seems to me overwhelming as a conviction. Only as you draw away from closeness to the actual scene can you think of what it means to doubt it. Only—the very force of this conviction does make the silence more dreadful, more impossible. That appalling silence of the poor body: it feels almost wilful, almost wicked.

Yet the body has the most amazing air of security about it. It carries peace with it: so smiling, so dignified, so assured, it lies on there. You cannot look at it and not recover some calm. It seems to pledge you everything: so full of benediction: sealed into silence and peace. All your trouble and wailing becomes like a childish matter, which is too tender to rebuke, but which it is waiting to laugh over on some future day; like we do over the passionate tears of a child.

There is a profound simplicity in the theology of death which emerges from the sermon, especially when it is read as a whole: there is the shock of the event itself, the terror of the unknown, but also the hope of personal continuity after death, and the sense of utter trust in God’s abiding love. This feeling cannot remove the shock or reduce the terror, but the sense of continuity is nevertheless able to reassure us of a sense of hope beyond hope, to express something of the simplicity of the Christian view of death. Something familiar will continue beyond death, and that something is now held by God. Our hope is in God whose care for us is greater than we can possibly imagine. If Scott Holland’s sermon can remind us of that, then it is still worth reading out at funerals. But we should never forget the first half – the serenity and hope are always accompanied by the terror and shock. The ‘appalling silence of the poor body’ is nevertheless ‘sealed into silence and peace’.